Dining with the Dead in the Ancient World

We go back to the ancient world to explore the rituals surrounding death and dinner.

Food has played a central role in death rituals for as long as humans have been around. Throughout history, food hasn’t only sustained life, it’s helped maintain a connection between the living and the dead. From Mesopotamian ghosts returning to earth in search of a meal, to Romans feeding their corpses with bread and wine, dining with our dead has helped us come to terms with loss. It’s helped us digest death.

Mesopotamia

According to ancient Mesopotamian literature, once a ghost entered the netherworld, things were pretty similar to when they’d been alive. Ghosts lived in houses and were reunited with family members who’d already passed on.

In reality, however, the netherworld was a dark and barren place, devoid of life. Food was believed to be ‘bitter’ and water ‘brackish’. For the dead, ‘dust [was] their food, clay their bread’. Ghosts therefore relied on food offerings from their living descendants.

In the Old Babylonian period (about 2000 - 1600 BCE), living relatives would leave food at the graves of the dead at the same time each month. If an offering was late or forgotten, the ghosts would return to the earth in search of sustenance, causing harm or misfortune to the living.

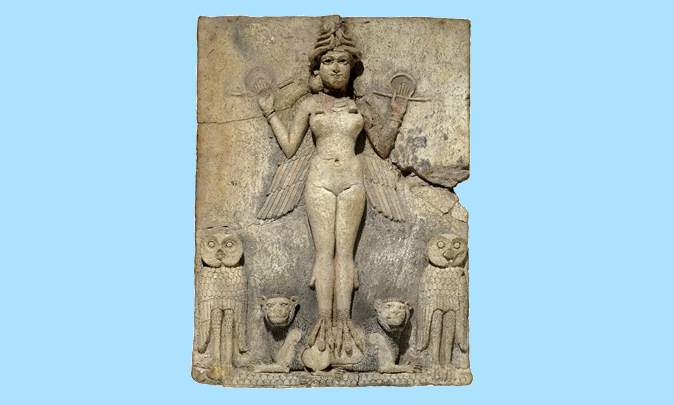

This relief, from around 1800-1750 BCE, could be the goddess Ishtar, Mesopotamian goddess of sexual love and war, or her sister and rival, the goddess Ereshkigal, ruler of the Underworld, or the demoness Lilitu, known in the Bible as Lilith.

Egypt

In Ancient Egypt it was common among royalty and nobility to have their servants, slaves and pets mummified alongside them, with the occasional bull, baboon or crocodile thrown in for good measure. But the dead also needed something to eat.

‘Meat mummies’ - literally mummified pieces of meat - were often buried alongside the departed to keep them full in the afterlife.

As far back as far 1386 - 1349 BCE (around 3,400 years ago), we find remains of mummified beef ribs and later examples of mummified goat leg (1290 BCE) and mummified calf (1070 - 945 BCE). In King Tutankhamun’s tomb, archaeologists found 48 cases containing cuts of beef and poultry. A feast fit for a king - though perhaps not enough for eternity.

A mummified beef rib from the tomb of Tjuiu, an Egyptian noblewoman, and her husband, the powerful courtier Yuya, circa 1386 - 1349 BC.

China

From the Neolithic period (around 5000 BCE) to the end of the Ming dynasty (1644 BC), it was customary for the Chinese to bury grave goods with their dead. This extended to food and drink, which was stored in containers to provide sustenance on the journey to the spirit world.

In 2016, a team of researchers uncovered a 3,100 year old tomb in China which contained various bronze soup bowls, alongside other ornately decorated food vessels. These were probably reserved for religious or burial ceremonies, rather than everyday meals. Either way, they're cool as hell.

This four-handled tureen was found in a 3,100 year old tomb and may have been used to serve soup. It's dotted with 192 spikes and is decorated with engravings of dragons, birds and bovines.

Greece

In ancient Greece, offerings known as enagísmata were made at the tombs of the deceased. Offerings included milk, honey, water, wine, celery, pelanós (a mix of meal, honey and oil) and kóllyba (dried and fresh fruits).

Animal sacrifices were also common - sheep, goats, fowl and, on special occasions, bulls. The animals were slaughtered over a trench, so, as one historian puts it 'the blood might run into the earth to appease the souls of the dead.’

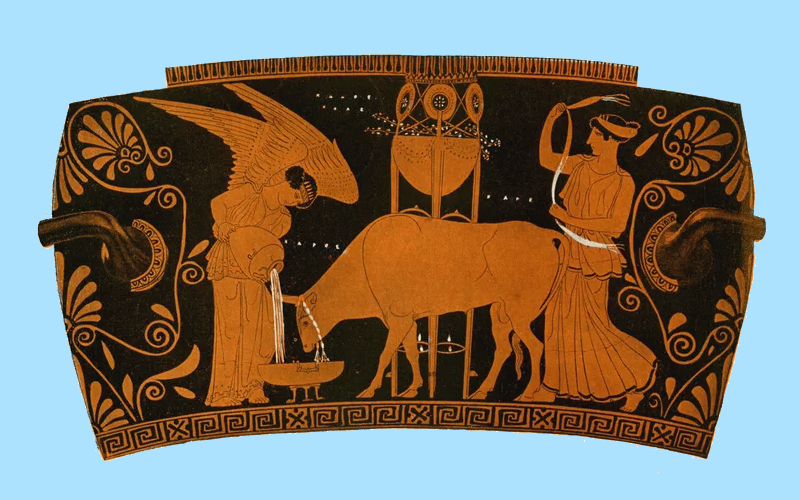

Athenian red figure vase showing women caring for a sacrificial bull, circa 5th century BCE.

Rome

In ancient Rome, funeral banquets were often held in front of the corpses before burial. In the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, Romans sacrificed a sow to Ceres, goddess of agriculture and fertility. The meat was shared between the deity, through burning it on a pyre, and the relatives, who ate it at the tomb. Stone seats were even incorporated into tomb and cemetery designs so people could dine with their dead.

The Romans also built tubes connecting the top of the grave with the crypt, allowing mourners to pour food and drink (mainly bread and wine) directly into the mouth of the corpse. This helped ‘feed’ the dead as they awaited the afterlife.

This skull of a Roman Gladiator was unearthed near the Coliseum in Rome and dates from 72 - 472 CE.