Mastic Fantastic: Resinating with history

Flavouring, chewing gum, cosmetic and medicine. The historical uses of mastic.

Chewy, resinous, pine-flavoured teardrops, used for thousands of years as a chewing gum, flavouring, medicine and beauty product. Welcome to mastic.

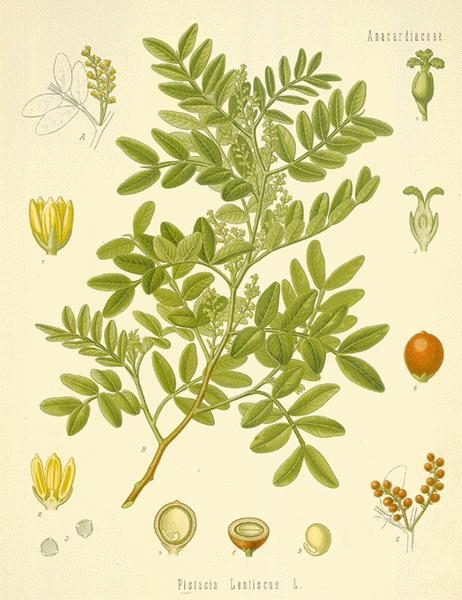

Mastic - also known as ‘tears of Chios’, and Arabic gum (see below for a breakdown of its many names) - is both the name of a Mediterranean tree and the aromatic resin it exudes. The tree (Pistacia lentiscus) is a member of the Pistacia genus in the cashew family and is closely related to the pistachio tree. The resin it produces, also called mastic, has been cultivated for at least 2400 years, particularly on the Greek island of Chios.

According to UNESCO, the harvesting of mastic is a ‘family occupation that requires laborious care throughout the year’. From around July, an incision is made in the bark of the tree where the resin collects and solidifies, creating tiny little drops or ‘tears’. When chewed, ‘tears of Chios’ have an initial bitter taste, followed by a pine- or cedar-like flavour.

Mastic in the ancient world

From perhaps as far back as 5000 years ago up until today, Egyptians have been using mastic to flavour a type of sausage, called Mombar Mahshy, which have been found in ancient tombs. In ancient Greece and Rome, people chewed the resin like a gum to help freshen their breath, which must have been pretty rank after all the fish sauce they were guzzling, though their actual teeth were probably healthier than ours. Hippocrates, the father of medicine, prescribed mastic to calm an upset stomach, while the Roman physician Galen thought it was good for bronchitis and improving the blood. Further east, in India and Persia, it was ingeniously used to fill dental cavities.

It appears that the ancients were onto something. Modern research into mastic suggests that it’s both an oral antiseptic and has the ability to target a type of harmful bacteria in the stomach. Not only that, it’s been shown to reduce cholesterol and have antimicrobial, antifungal, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties. It seems those doctors living thousands of years ago weren’t entirely off the mark when they recommended a good dose of tears to make everything better.

Mastic had many uses throughout antiquity, including in cosmetics. Dioscorides, writing in the 1st century AD, noted that Greek women used the resin to attach fake eyelashes. When the island fell under Ottoman control around 1566, the mastic industry was considered so important by the colonists that the villages which produced it were given special privileges and protections. Perhaps this was because the sultan’s harem used it as a cherished part of their beauty regimes, to freshen their breaths and whiten their teeth (or so the story goes). In Turkish, the island of Chios is still called Sakiz Adasi, translating to ‘island of gum’.

Mastic, the Mediterranean and the Middle East

Mastic has been used for hundreds of years in many Mediterranean and Middle Eastern desserts, including pastries, puddings, ice creams, and cakes, and it also occasionally crops up as a setting agent in Turkish delight recipes.

The resin creeps up in early versions of now-popular desserts, including the medieval Arabic pastry lauzinaj, which closely resembles baklava. One variation called for ‘the thinnest of the thin bread’, flavoured with mastic and rosewater and stuffed with almonds and sugar. Rather than being baked, it was fried in almond oil and if cooked properly would have melted in the mouth as soon as it touched the tongue.

Other Middle Eastern desserts were perfumed with mastic, along with rosewater, musk, camphor and ambergris. There was the nougat-like confection nātif, made from honey, egg whites and nuts and scented with musk, ambergris and mastic. The Abbasid prince, Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi (779–839), a renowned poet, musician and cook, was so inspired by some sesame cookies flavoured with mastic and saffron he dedicated a poem to them:

Shaped like perfect discs of equal size, each of which the full moon resembles.

As luscious as honey they taste and like the breeze sweetly perfumed.

Like silver and gold, white and yellow juxtaposed.

Mastic and meat

But mastic wasn’t only confined to its use in desserts. In the medieval Arabic cookbook, Kitab al-Tabikh, written in 1226, the author includes the resin in more than half of his 96 recipes for red meat. Muhammad b. al-Hasan al-Baghdadi, the author, even insisted that you should always boil and then fry chicken in a mixture of cinnamon, coriander and mastic before adding any other ingredients. Other recipes included kid cooked with vinegar, celery leaves, mastic and saffron, called masus, and roast fish sprinkled with coriander, cinnamon, cumin and mastic, known as samak mashwi.

Mastic and the modern world

According to food historian Charles Perry, Egypt is the only modern-day nation (to his knowledge) that still uses mastic in savoury dishes, which often appears in recipes for chicken, duck, rabbit, fish and tripe.

When it comes to sweet treats, ‘tears of Chios’ often creep up in particular types of ice cream, such as the Greek kaimaki, Turkish dondurma and the Arabic booza varieties. These ice creams are traditionally made with sweetened milk flavoured with mastic and thickened with the powdered bulbs of wild orchids. This type of ice cream is much thicker, chewier and more elastic than the kind we’re familiar with in the West. In fact, at times it’s so thick you need a knife and fork to eat it. In Turkey, street vendors use metal paddles to whip the ingredients together and will often dip the cones in crushed pistachios.

There’s also the Greek liquor, mastika, which is similar to ouzo, as well as the similar (though distinct) Chios Mastiha, a drink which now has protected designation of origin status within the EU.

And in recent years the ingredient has been gaining in popularity further West. In 2017, Vogue online labelled mastic liquor the ‘must-try cocktail ingredient’, while in 2012 the Telegraph included a recipe for chicken roasted in mastic and pomegranate molasses. And profiles of the resin have popped up on food websites, such as Saveur and Food Republic.

Is mastic the next superstar of the food fad scene? Probably not. But mastic is, by all accounts, fantastic. It’s unusual flavour, it’s extensive history, its use in sweet and savoury dishes, as well as in medicine, beauty and as a chewing gum, make those little ‘tears of Chios’ something to seek out and sample, if only to sate your curiosity.

Mastaken identity: The many names of mastic

To keep things interesting, mastic goes by more than one name. Here’s a break down so you don’t get confused:

Mastic

The word ‘mastic’ has the same roots as the English ‘masticate’, and literally means, ‘to gnash one’s teeth’. Interestingly, the modern word for chewing gum in Greek is ‘chicle’. Chicle, it so happens, is the name of the sap of the sapodilla tree, which ancient Mayans used as their own version of chewing gum, which helped them to quench thirst and stave off hunger. And it’s chicle that became the base when modern chewing gums were developed.

Tears of Chios

The resin is traditionally produced on the Greek island of Chios (pronounced hee-oss). Some say mastic can only come from Chios, which isn’t actually true, but it is the only place where a particular variety grows (Pistacia lentiscus Chia or Latifolia) and that’s the kind that’s used in a variety of Mediterranean food. What’s with the tears? This is a reference to the way the resin dries into crystal-like beads, reminiscent of teardrops.

Arabic gum

Don’t get this confused with gum arabic, the resin of another tree historically cultivated in West Africa and Arabia.